“Why are you crying, dad?”

Odd One Out / part 2

One Sunday like any other, our family of five gathered around the dining table, The roast lamb steaming on the platter. Knives, forks, and two wine glasses, all waited. My father, overly solemn and strained, bowed his head and recited Grace—a ritualistic string of words, more habit than heartfelt.

After that we all extracted the tightly held white napkins, rolled in coiled bamboo rings, designed to resembled snakes. Their red fake-jewel “eyes” glinted like something out of a spooky cautionary tale.

To my young, impressionable mind, they were icons—lodestones—that foretold something ominous. Symbols. Warnings. Metaphors waiting to come alive in the theatre of our domestic life.

The radio was tuned to Desert Island Discs. Roy Plumley, the ever-courteous BBC presenter, introduced his guest and began the familiar interview about life and music.

Theme tune to: Desert Island Discs Theme Tune

Snippets of compositions played, woven between stories of influence and identity. That Sunday, the chosen “castaway” selected a piece that would change everything in our house: Scenes from Childhood by Robert Schumann.

Something in my father buckled. He began to weep.

Not the discreet, dignified kind of weeping men sometimes allow themselves. These were wrenching, guttural sobs—grief gushing through the fractured dam of decades.

We, his young sons, had never seen him like that. Not broken. Not human in this way. His tears kept falling, unstoppable and strange. The roast went cold. None of us dared touch our plates. None of us dared speak.

But I, always the questioner, couldn’t bear the silence.

“Why are you crying, dad?”

And then came his shocking and sad story. Other than our mother, we three lads were not prepared for what was to come next. And what he said would reframe not only that Sunday afternoon, but much of my life.

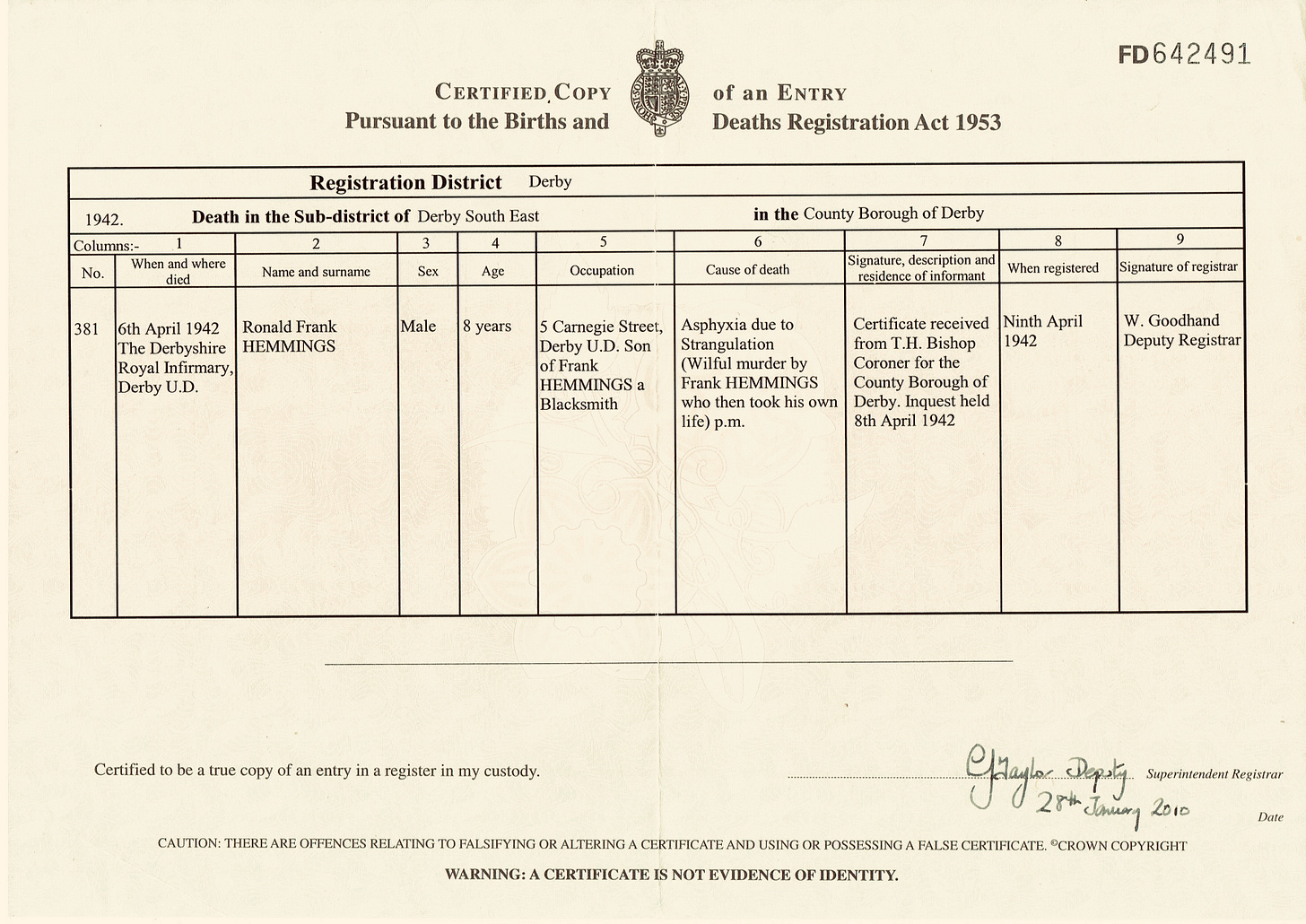

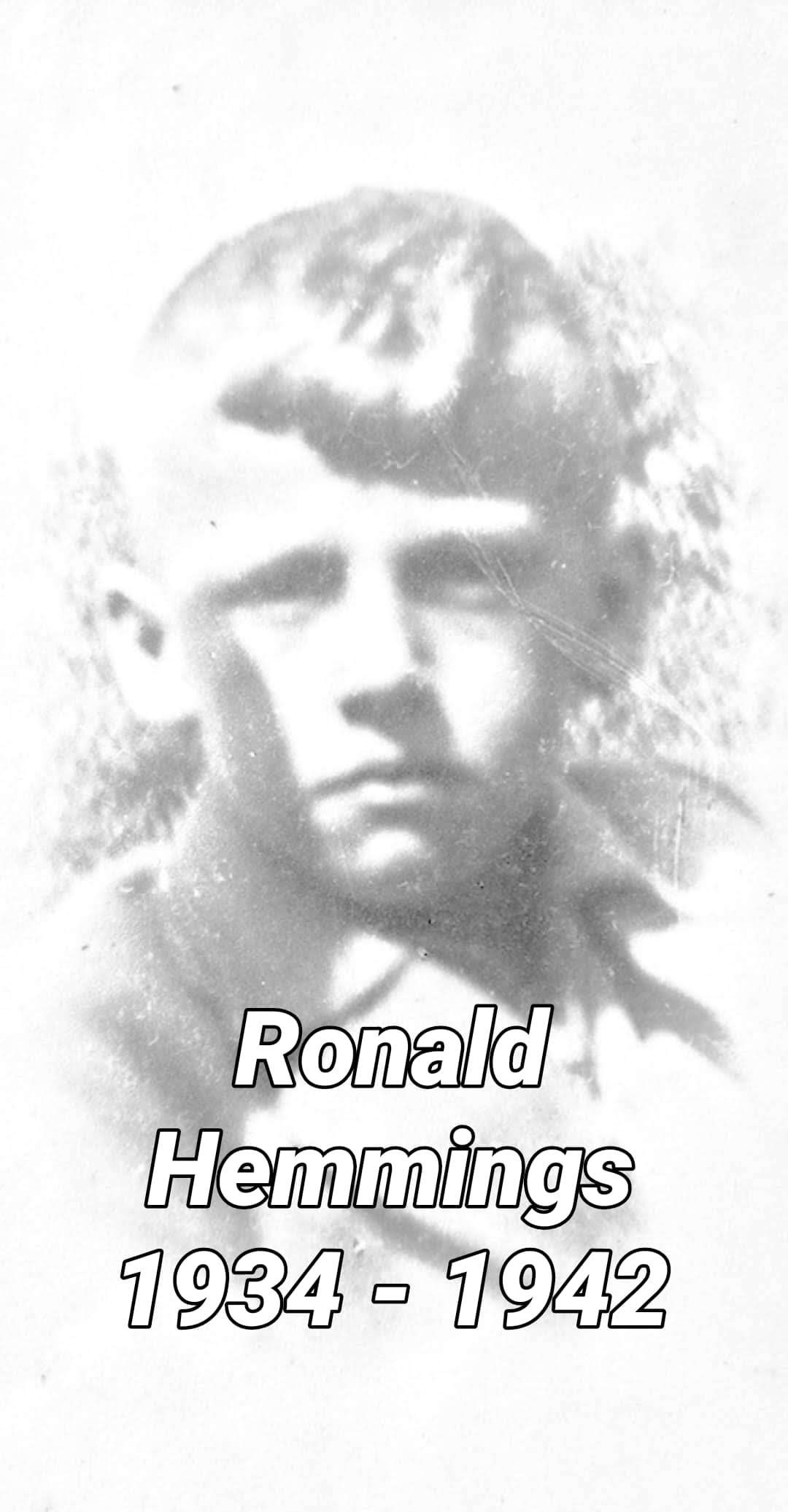

Ronald, my teen father’s eight year old brother had been killed. I was that same age as him. He had been “unwell,” left one evening in the care of their father, Frank. My grandmother Doris had gone next door to borrow the Derby Telegraph.

When she returned, a note was pinned to the boy’s door: “Do not enter. Call the police.”

Inside, Ronald was dead—smothered, my father said.

But the coroner’s report contradicted that version. It stated “death by asphyxiation”—not by suffocation, but by strangulation. A far darker truth. The inquest and the subsequent double funeral were covered in Midlands newspapers.

My father, in his mid teens, was thrust into a cold spotlight. That exposure, that unspeakable shame, became his inheritance. It etched itself into his psyche like acid into stone. From that day forward, he carried a persecution complex—paranoid, brittle, vigilant. He joined a fellowship no one would ever choose: the quiet fraternity of those marked by scandal and grief.

No other kid on my street had a murder-suicide event in their family, that I knew of. That became my dubious distinction. The kind of thing whispered, never spoken aloud. A shadow that moved in before I even understood its shape.

And if that wasn’t enough, I sometimes imagined myself secretly tattooed — not with ink, but with something stranger, surreal. A mark no one could see. It was an invisible shame mark, proof I was somehow cursed. Other times, it became a secret seal, like I’d been chosen for something too strange or sacred to explain.

Either way, I was marked.

That mark made me different, and different became my identity. Not quirky-different, not interesting or cool. Odd. Odd in the way people avoid. Odd in the way no one quite knows how to love. I didn’t know it then, but I carried that difference like a banner and a burden — part shield, part scar.

No one else wore what I wore. No one else bore what I bore. Not on my street anyway.

KatyaZhu.com

Thirty years later I would write a painful, prescient poem about this ugly reluctant inheritance. It was my coroner’s trial but by verse:

Did you hold his life so lightly, him on whom you used to dote? You squeezed so terribly tightly on that sick child's small throat.

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found

That same evening, my grandfather Frank ended his own life. He walked, as if on some grim pilgrimage, to a canal bridge. Tied a piece of angle iron around his neck. Jumped. A police sergeant’s torch later found his floating trilby hat at midnight, drifting gently like a ghost on the surface of the water.

Did you linger before you leapt? Did any witness your bitter end? Were any repentant tears wept? Did you struggle, or calmly descend?

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found

Was the suicide of Frank a “Rumpelstiltskin suicide” - the act of a narcissist who can’t reconcile his grandiose sense of self with reality. One other question now comes to mind. Did their two bodies lie side by side on mortuary trolleys in the hospital, observed by shocked staff, mourned by invisible angels?

Earlier that day, my teen father had been out cycling in the countryside, dreaming of girls and composing poetry. When he returned, he may have discovered the body. He may not. The versions varied over the years. What remained consistent was the denial. He refused to believe the coroner, the police, the newspapers. As if his truth could reverse the act.

I noticed something strange—subtle numerical distortions, discrepancies carved in stone. My grandfather’s age was listed as forty-two. But his death date—April 6, 1942—was oddly omitted. Ronald’s birth and death, by contrast, were clearly inscribed. The stone bore a mixed metaphor:

“Jesus has him in a better place.”

But who exactly was “him”? Ronald, I presumed. Surely not Frank.

I discovered that my (later remarried) grandmother, was in the same grave but unnamed on the stone. She had also died by suicide—an overdose of Barbitone in a psychiatric hospital.

In 2010 I replaced that slyly worded stone with a new, bigger, braver memorial block. Ronald’s name was placed at the centre, his parents on either side. On sloped top of the memorial cube are the healing, hopeful words from Revelation 21:4:

“He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more...”

These stories—somewhat sanitised—shaped much of my psychological formation. This was the weight I inherited. This was the silence I had to fill—with words.

And looking back now, I wonder:

Should my childhood questions have been answered at all? Should they have been answered so bluntly, so completely?

Why didn’t my mother intervene—step in to protect us from the weight of our father’s unprocessed sorrow?

Did my father ever grasp the emotional burden he placed on me that day—his eight-year-old son—when he handed me the family’s darkest truth like it was mine to carry?

What a heart-wrenching story, Louis. I can hardly imagine what it must have been like to live through that as a child. My maternal grandfather murdered my grandmother when my mom was just three years old. As an only child, she went to live with her grandmother. The feelings you describe really resonated — my mom even faced cruel taunts from other children calling her “the murderer’s daughter.” As if what happened wasn’t bad enough.

She never told my brother or me about it; I only found out when I was about fifty, after a family member spoke to me – thinking I knew. My poor mother was devastated that I found out — she’d always said her parents died in a car accident. Learning the truth didn’t affect me directly, but it gave me a much deeper understanding of what she must have carried all her life.

Thank you for sharing your story — it brought up a lot, but also made me feel strangely connected in recognising some of those same echoes across generations.